Jump to...

Non-EU banking groups (“non-EU groups”) with large EU operations will be required to establish an EU intermediate parent undertaking (“IPU”) according to the final changes to the Capital Requirements Directive (“CRD 5”) package.[1] CRD 5 will enter into force 20 days after it is published in the Official Journal of the European Union, which is likely to be in Q2 this year, and will apply 18 months thereafter. The new rules are similar to U.S. Federal Reserve requirements for certain non-U.S. banking organizations to establish an intermediate holding company (“IHC”) in the United States. Non-EU groups will need to hold EU bank and investment firm subsidiaries through one, or at the most, two EU IPUs. Each EU IPU will be subject to capital, liquidity, leverage and other prudential standards on a consolidated basis.

This note discusses the key obligations and impacts for non-EU groups and their restructuring plans, with a particular reference to U.S. and U.K. groups. We also discuss the potential interactions between Brexit and these new requirements for U.K. sub-groups.

The final text of the IPU rules differs substantively from the original proposals published by the European Commission in November 2016.[2] Four significant, and welcome, changes it introduces are:

Large non-EU headquartered financial groups will need to analyze how to comply with the new EU IPU requirements—in particular, any new governance or other prudential requirements—and remain in compliance with their home country’s rules. Such groups will also need to consider how to structure their operations, including evaluating whether only one EU subsidiary is needed. For some groups, it may be easier to change the scope of their activities or reduce their balance sheets in the EU to ensure that they fall below the relevant threshold such that the new IPU rules do not apply to them.

According to the Commission, the EU IPU rule is intended to ensure that the EU operations of non-EU groups are sufficiently capitalized so, if the group fails, there is enough capital locally to absorb the losses of the group’s European operations. It also fills a gap by providing the Single Resolution Board with the requisite resolution supervisory tools for those firms established in the Eurozone. However, it is widely regarded as retaliation to the Federal Reserve’s requirement for non-U.S. banking organizations above a certain asset threshold to establish a U.S. IHC. That U.S. requirement resulted in many large EU-headquartered banks undertaking major restructurings at significant cost to maintain (non-branch) access to the U.S. market. The Federal Reserve’s IHC rule was widely viewed as addressing the capital position of large U.S. broker-dealer subsidiaries of non-U.S. banks because such broker-dealers were not otherwise subject to a risk-based and leverage capital regime administered by U.S. prudential banking regulators. By contrast, the large EU broker-dealer subsidiaries of U.S. bank holding companies are currently subject to Basel-based capital requirements and so the same rationale for the EU rule, whilst asserted, is elusive. Moreover, the Federal Reserve’s rule may be revisited in its anticipated rulemaking to apply tailored legislation to non-U.S. banking organizations.

Where a non-EU group has two or more banks or investment firms established in the EU, it would need to set up an intermediate EU parent undertaking above those entities. A non-EU group is one that has at least one subsidiary EU bank or large EU investment firm in its group and the parent entity is established in a non-EU country.

Non-EU groups within scope of the EU IPU rules are those that have a total value of assets of more than €40 billion in the EU. The threshold is higher than the €30 billion originally proposed by the European Commission. However, it is still lower than the U.S.’s equivalent $50 billion threshold. The total value of assets for purposes of the EU test takes into account: (i) the assets of the group’s EU bank and investment firm subsidiaries; and (ii) its EU bank and investment firm branches (even though branch assets are not required to be moved into the EU IPU). This is in contrast to the U.S. IHC rule, which looks only at U.S. non-branch assets because only non-branch assets are subject to being placed under the U.S. IHC.

Each EU IPU would need to obtain authorization as either a bank under CRD 5, or alternatively be approved as a financial holding company under related new provisions bringing financial holding companies directly within the scope of the EU prudential regulation regime.[4] The IPU may alternatively also itself be an investment firm authorized under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (“MiFID II”) and subject to the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive if either: (i) none of the third-country group’s EU entities is a bank; or (ii) it has to be an investment firm to comply with a third country’s mandatory separation requirements. Regardless of the type of entity, this will trigger an authorization process for the EU IPU which will become subject to the direct supervision of the relevant national regulator or the European Central Bank (if the IPU is established in the Eurozone).

The amendments allowing two IPUs will be welcomed by U.S. groups that have separate bank and non-bank sub-groups and that must comply with U.S. restrictions on the activities that each can undertake. This change will also allow U.K. banking groups to comply with the new U.K. ring-fencing rules once the U.K. has left the EU.

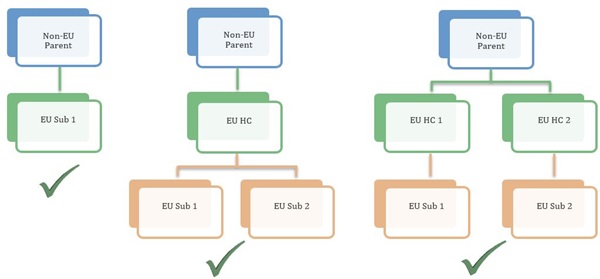

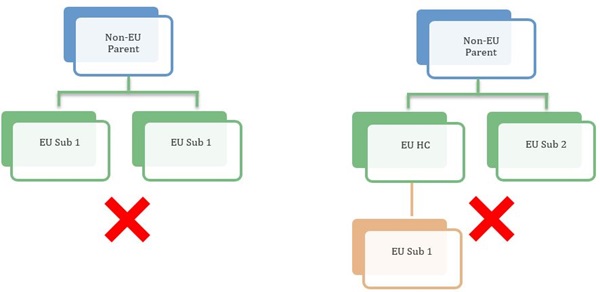

The diagrams below illustrate at a high level the structures that will or will not be permitted under the EU IPU rules.

Examples of permitted structures

Examples of prohibited structures

CRD 5 includes a transitional provision for non-EU groups that already have large EU operations on the date that CRD 5 enters into force.[5] These groups will have three years from the date that CRD 5 becomes applicable to establish an EU IPU.[6] This transitional provision is relevant to the timing of Brexit because the requirement to establish an EU IPU will only become applicable after the U.K. is scheduled to leave the EU, either in a “no deal” scenario or if an agreement is reached. If Brexit is delayed, this situation may change, depending on the extent of the delay.

Issues for Non-EU Groups (excluding UK Groups)

Where the U.K. has left the EU by the time CRD 5 applies, the U.K. subsidiaries of a non-EU group will not need to be taken into account to determine whether the group is within scope of the IPU requirements. Likewise, the U.K. branches of a non-EU group will be irrelevant for the threshold calculation. In the event that Brexit is delayed and the U.K. is still an EU Member State when CRD 5 enters into force, then U.K. subsidiaries and branches would need to be factored in, but only for such time as the U.K. remains an EU Member State. In the delay scenario, to avoid a situation where a group would only be within scope of the EU IPU rules until the U.K. leaves the EU, non-EU groups would be reliant on the Commission or individual EU Member States passing legislation allowing their U.K. entities to be ignored for these purposes for the interim period.

Issues for UK Groups

Once the U.K. leaves the EU, U.K. groups fulfilling all the EU IPU conditions would be in-scope and would need to set up an EU IPU. In the event of a no deal or an agreed Brexit, the transitional provisions would apply to these groups, giving them time to structure themselves appropriately. However, if there is a Brexit delay, it is unclear whether the transitional provisions would apply to U.K. groups, although one would hope that they would to avoid uncertainty and risks to financial stability.

Non-UK Groups and UK Legislation Post-Brexit

The U.K. has prepared draft legislation[7] that would give HM Treasury, in a no deal scenario, powers to implement and make amendments to a specified list of financial services “in flight” legislation. This refers to EU financial services legislation that is out of scope of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 because it will not be “operative” before exit day. Only legislation with an implementation date falling in the two years after the U.K.’s exit is covered. CRD 5 is within scope of this draft legislation. However, to our knowledge, the EU IPU requirements are not part of the U.K.’s financial services policy.

Possible Future EU Amendments

The European Commission is required, within a set number of years of CRD 5 becoming applicable, to review the EU IPU rules and report on whether the rules reflect “best international practices.” This will likely include comparisons with the U.S. IHC rules and a consideration of the post-Brexit environment.

The new EU IPU obligation does not require subsidiarization of the EU operations of non-EU groups that are conducted through EU branch offices. The ECB advocated the extension of the requirements to third-country branches regardless of whether a non-EU group operates in the EU partially or exclusively through branches and called for existing branches exceeding a certain threshold to be reestablished as branches of the IPU.[8] The ECB’s extension proposals were not adopted. However, the final text does require, within two years of CRD 5 entering into force, the European Banking Authority to report to the European legislative bodies on the treatment of third-country branches under relevant national laws of member states. The report must consider the extent to which those national laws differ across the EU, whether any such difference opens the door for regulatory arbitrage and whether it would be appropriate to introduce further harmonization, in particular, on the treatment of significant third-country branches.

Large U.S. bank holding companies operate in the EU through direct branch offices of their home country subsidiary FDIC-insured banks as well as through locally incorporated bank subsidiaries of those banks and, importantly, through broker-dealer subsidiaries that are often (but not always) owned by the bank holding company through a corporate chain separate from the FDIC-insured bank. There are strict limitations on transactions (including loans and other funding transactions) between the FDIC-insured bank (and its subsidiaries) on the one hand and its bank holding company parent and sister companies on the other. There are also limits on the securities underwriting and dealing activities of a broker-dealer subsidiary of a U.S. bank, which can make it impractical or difficult to operate a large broker-dealer as a direct or indirect subsidiary of a U.S. bank. Thus, the largest U.S. bank holding companies operate their large U.S. broker-dealer subsidiaries as sister companies of their FDIC-insured banks and often do the same with their non-U.S. broker-dealer subsidiaries.

Moreover, the swap push-out provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act (as amended) prohibit U.S. banks (and their subsidiaries) from engaging in certain types of structured finance swap transactions. It is to be expected that U.S. institutions subject to these requirements will be able to establish two IPUs, one for the bank chain and another for the non-bank chain.

This table sets out the main differences and similarities between the existing U.S. IHC rules for FBOs and the incoming EU’s IPU rules.

| U.S. IHC RULES FOR FBOS | EU IPU RULES FOR THIRD-COUNTRY BANKING GROUPS | |

| Scope | Despite different capital requirements regimes in the U.S. for banks and broker-dealers ("b-ds"), the U.S. IHC rules for FBOs brought some b ds into the bank capital rules by making the IHCs subject to bank capital rules on a consolidated basis and requiring the b-ds entities to become subsidiaries of such IHCs (which increased costs). | Applies to non-EU banking groups with two or more banks or investment firms established in the EU. |

| Threshold | U.S. non-branch or agency assets of US$50 bn or more. It is possible that this threshold may be raised in light of other recent increases in prudential thresholds in the United States. | A non-EU group that has two or more banks or investment firms established in the EU and that has total EU assets of at least €40 bn (bank and investment firm subsidiaries and branches). |

| Applicable to all foreign G-SIIs | No, not automatic. | No, not automatic. |

| Single IHC/IPU requirement | Yes, subject to certain exceptions. | Yes, subject to an exception allowing for two IPUs where a third-country's laws require this (see exceptions). |

| Form of IHC/IPU | An IHC is typically a U.S. corporation or limited liability company. No particular form is mandated, but an IHC must be governed by a board of directors or managers that has rights, powers, duties, etc. similar to those of a company chartered as a corporation under U.S. law. No particular financial activity license is required but often is a financial holding company (FHC) under U.S. law. | The IPU must be either an EU authorized bank or an approved financial holding company or mixed financial holding company. A derogation allows for the IPU to be an investment firm authorized under MiFID II where: (i) none of the EU entities are banks; or (ii) two IPUs are allowed and the second IPU needs to be an investment firm to comply with the ultimate parent's home country laws. |

| Ownership interests / transfer requirements | Yes. Ownership interests in virtually all U.S. bank and non-bank subsidiaries must be transferred to the U.S. IHC. U.S. branch and agency offices of non-U.S. banks do not need to be transferred, rolled up or otherwise "subsidiarized." | All bank and investment firm subsidiaries must be owned by the new EU IPU. There is no subsidiarization, transfer or roll-up requirement for EU branches of non-EU banking groups. |

| Exceptions | U.S. Federal Reserve may allow alternative ownership structures if applicable home-country law prohibits the FBO from controlling its U.S. subsidiaries through a single IHC or where the activities, scope of operations or structure of the U.S. subsidiaries justify an alternative structure. Limited availability.[9] | National regulators may allow two IPUs to be established where a single IPU would be "incompatible with a mandatory requirement in accordance with the rules of the third country where the ultimate parent undertaking of the third country group has its head office." More commonly expected. |

| Other requirements | A U.S. IHC must comply with U.S. Basel III leverage capital requirements, capital planning, stress testing, liquidity requirements and risk management requirements, such as establishing a risk committee. | Dependent on whether the EU IPU is authorized as: (i) a bank; (ii) an investment firm; or (iii) a financial holding company. |

[1] The text of CRD 5 was agreed between the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union on February 15, 2019. This client note is based on that version of CRD 5 as amended by the text of the new Investment Firm Directive, which was agreed between the two legislative bodies on March 19, 2019 (and which confirms that change to the definition of "institution" in the Capital Requirements Regulation will not affect the scope of the EU IPU requirements). There may be minor drafting changes as the text is vetted by technicians and translated prior to its publication, but the legal position should be unaffected by this.

[2] On November 23, 2016, the European Commission published legislative proposals to amend the Capital Requirements Directive and the Capital Requirements Regulation as well as other key pieces of EU banking legislation.

[3] This derogation was suggested by the ECB in its Opinion on amendments to the Union framework for capital requirements of credit institutions and investment firms (CON/2017/46), OJ C 34, 31.1.2018, p. 5.

[4] New Article 21a, CRD.

[5] CRD 5 enters into force 20 days after it is published in the Official Journal of the European Union.

[6] CRD 5 will enter into force 20 days after it has been published in the Official Journal of the European Union. The European Commission had proposed a delay of two years after the revised CRD entered into force. However, according to HM Treasury, the U.K. government succeeded in securing an extension to that deadline. See the letter from HM Treasury to the head of the European Scrutiny Committee.

[7] At the time of writing the draft Financial Services (Implementation of Legislation) Bill is being considered by the U.K. Parliament and the provisions are therefore subject to change. The progress of the Bill can be tracked here. HM Treasury published a Policy Note explaining the purpose of the Bill.

[8] ECB Opinion on amendments to the Union framework for capital requirements of credit institutions and investment firms (CON/2017/46), OJ C 34, 31.1.2018, p. 5.

[9] On February 14, 2018, the U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System used its authority for the first time and approved the establishment by Deutsche Bank AG of a second U.S. IHC to hold its asset management business pursuant to Regulation YY. You may like to view details of the approval.