Jump to...

In the transition to cleaner and more secure domestic energy sources, offshore wind presents a significant opportunity for local economic growth and job creation. Notably, on June 8, 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) announced its intent to assess potential opportunities to advance clean energy development on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf. This article discusses opportunities and challenges for offshore wind in the U.S., the Biden administration’s goals, and a comparison of offshore oil & gas leases vs offshore wind leases.

Offshore wind has the significant advantage of being located close to population centers along the coast of the United States. Locating offshore wind farms near populated or industrial areas can help reduce the amount of energy sourced from non-renewable sources. Offshore wind serves as a compelling alternative to long-distance transmission of onshore electricity generation.[1]

Data suggests that over 2,000 gigawatts could be accessed in state and federal waters along the coasts of the United States and the Great Lakes. Though only a portion of the technical resource potential will realistically be developed, “the magnitude (approximately two times the combined generating capacity of all U.S. electric power plants) represents a substantial opportunity to generate electricity near coastal high-density population centers.”[2]

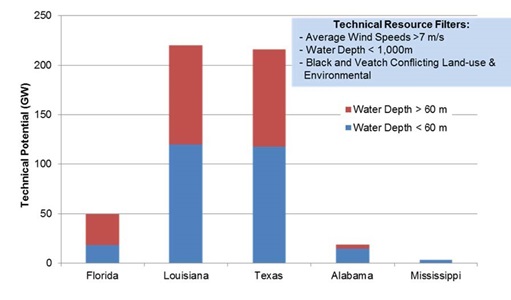

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) evaluated multiple clean energy technologies for resource adequacy, technology readiness and cost competitiveness and found that offshore wind in the Gulf of Mexico has the highest technical resource potential—508 gigawatts.[3] In particular, significant potential lies off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. “The Gulf Coast States comprise 32 percent of the shallow-water offshore wind potential in the United States, with the highest potential wind resources off the Texas and Louisiana coasts.”[4] It is estimated that, “if current cost trends observed in Europe and the northeast United States …continue, the economics of offshore wind in the Gulf of Mexico over the next decade will approach positive net values in…Texas and Louisiana.”[5]

Offshore wind technical resource potential in the Gulf of Mexico[6]

On January 27, 2021, President Biden signed Executive Order 14008, “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.” The Executive Order provides for a review of the siting and permitting processes in offshore waters to increase renewable energy production in those waters.[7] The Executive Order commits to expand opportunities for the offshore wind industry and double offshore wind in the United States to 30 gigawatts by 2030.[8]

The Executive Order directs the Secretary of the Interior to halt new oil and gas leasing on public lands and offshore waters pending completion of a review of federal oil and gas activities, including climate and other related impacts.[9] In response, on February 12, 2021, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) announced its rescission of the Record of Decision for the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Lease Sale 257 (Lease Sale 257). Lease Sale 257 was to be the eighth offshore sale pursuant to the 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Lease Program. The decision suspends planning for the proposed sale that was expected to occur in March 2021.[10]

Following the DOI’s announcement that it will be assessing opportunities to advance clean energy development on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf, on June 11, 2021, it issued a Request For Interest (RFI) commencing a 45-day public comment period to “solicit indications of competitive interest and additional information on potential environmental consequences and other uses of the proposed area.”[11] The RFI is focused on the Western and Central Planning Areas of the Gulf of Mexico offshore, the states of Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama, and the primary focus of the RFI is on wind energy development.[12] The deadline for submissions related to the RFI is July 26, 2021.[13] Following the public comment period, BOEM will review the information received from the RFI to determine its path forward with respect to the renewable energy leasing process in the Gulf of Mexico. Depending on the feedback received, BOEM will either proceed with a competitive lease sale or issue a non-competitive lease.[14] As part of the determination process, BOEM held its first Gulf of Mexico Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force meeting on June 15, 2021. The task force includes members representing federal, Tribal, state and local governments from Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi and Alabama.[15] The Task force is intended to bring together members to “coordinate and share information on proposed offshore renewable energy-related activities in federal waters in the Gulf of Mexico.”[16]

Both the BOEM Oil and Gas Lease of Submerged Lands Under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (Offshore O&G Lease) and the BOEM Commercial Lease of Submerged Lands for Renewable Energy Development on the Outer Continental Shelf (Offshore Wind Lease) are issued pursuant to the Outer Continental Shelf Act. However, the Offshore O&G Lease and Offshore Wind Lease differ in various ways, as described below:[17]

The barriers to offshore wind development continue to include the mitigation of impacts on the environment, the technical challenges of installation, and the challenges related to grid interconnection.[20] Environmental surveys, monitoring tools and resources are employed to understand the impact of offshore wind construction on wildlife and marine life. This information can be used to guide energy developers on how to implement sustainable ocean energy projects.[21] Due to the nature of offshore wind projects, there is an increased risk for corrosion and damage to the offshore wind systems. As such, the systems must be designed to withstand the wear and corrosion that results from exposure to seawater.[22] Finally, operating changes and equipment upgrades will likely be required to facilitate and integrate offshore wind on a widespread basis.[23]

[1] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. “Renewable Energy on the Outer Continental Shelf.”

[2] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, Wind Energy Technologies Office. “Offshore Wind Research and Development.”

[3] Musial W, Beiter P, Stefek J, Scott G, Heimiller D, Stehly T, Tegen S, Roberts O, Greco T, Keyser D (National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, Golden, CO). 2020. Offshore wind in the US Gulf of Mexico: regional economic modeling and site-specific analyses. New Orleans (LA): Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. 94 p. Contract No.: M17PG00012. Report No.: OCS Study BOEM 2020-018.

[4] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. June 8, 2021. “BOEM Gulf of Mexico Regional Task Force Meeting on Renewable Energy.”

[5] Musial W, Beiter P, Stefek J, Scott G, Heimiller D, Stehly T, Tegen S, Roberts O, Greco T, Keyser D (National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, Golden, CO). 2020. Offshore wind in the US Gulf of Mexico: regional economic modeling and site-specific analyses. New Orleans (LA): Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. 94 p. Contract No.: M17PG00012. Report No.: OCS Study BOEM 2020-018.

[6] Id.

[7] The White House. January 27, 2021. “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.”

[8] The White House. March 29, 2021. “Fact Sheet: Biden Administration Jumpstarts Offshore Wind Energy Projects to Create Jobs.”

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. May 10, 2021. “Secretaries Haaland and Raimondo to Make Clean Energy Jobs Announcement, Discuss Progress on Offshore Wind Development.”

The White House. January 27, 2021. “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.”

[9] 86 FR 10132, February 18, 2021. “Gulf of Mexico, Outer Continental Shelf, Oil and Gas Lease Sale 257.”

[10] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. February 12, 2021. “BOEM Rescinds Record of Decision for Gulf of Mexico Lease Sale.”

[11] U.S. Department of the Interior. June 8, 2021. “Interior Department to Explore Offshore Wind Potential in the Gulf of Mexico.”

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. June 11, 2021. “Request for Interest in Commercial Leasing for Wind Power Development on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).”

[12] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. June 11, 2021. “Request for Interest in Commercial Leasing for Wind Power Development on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).”

[13] Id.

[14] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. June 11, 2021. “Request for Interest in Commercial Leasing for Wind Power Development on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).”

Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA), 43 U.S.C. 1337(p)(3). The OCSLA requires BOEM to award leases competitively, unless BOEM determines that there is no competitive interest. If the RFI, reveals that there is no competitive interest in the RFI Area, BOEM may initiate a non-competitive leasing process under 30 CFR 585.232. However, if the RFI, results in competitive interest in any portion of the RFI Area, BOEM may proceed with the competitive leasing process under 30 CFR 585.211 through 585.225.

[15] U.S. Department of the Interior. June 8, 2021. “Interior Department to Explore Offshore Wind Potential in the Gulf of Mexico.”

[16] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. June 8, 2021. “BOEM Gulf of Mexico Regional Task Force Meeting on Renewable Energy.”

[17] U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. “Oil and Gas Lease of Submerged Lands Under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act.”

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. “Commercial Lease of Submerged Lands for Renewable Energy Development on the Outer Continental Shelf.”

[18] 30 CFR 585.503.

[19] Id; 30 CFR 585.506.

[20] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, Wind Energy Technologies Office. “Offshore Wind Research and Development.”

[21] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, Wind Energy Technologies Office. “Offshore Wind Market Acceleration Projects - Environmental Surveys, Monitoring Tools, and Resources.”

[22] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, Wind Energy Technologies Office. “Offshore Wind Research and Development.”

[23] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, Wind Energy Technologies Office. “Offshore Wind Market Acceleration Projects – Transmission Planning and Interconnection Studies.”

Practices