Jump to...

The Supreme Court has upheld the High Court’s decision in Miller v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union. Its judgment confirms that an Act of Parliament is required to authorise the Government to begin the process of the UK leaving the EU under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. Political indications are that the House of Commons is likely to approve the bill, following their motion on the same topic last year. The position of the House of Lords is less certain. This memorandum analyses the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision and discusses the options available to the Government.

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (“TEU”) provides that a member state may withdraw from the EU by notifying the European Council of its intention following a decision made “in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.” The UK Government had argued that the European Council could be notified by the Government under the royal prerogative.[1] This argument was rejected by the High Court in Miller v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, which held that an Act of Parliament was required.[2] That decision was appealed to the Supreme Court.[3] For the first time ever, all eleven members of the Supreme Court heard the appeal, reflecting the constitutional and political importance of the case.

In upholding the decision of the High Court, and confirming that the Government lacks the legal authority to trigger Article 50 without statutory authority, Lord Neuberger, writing for the majority in an 8-3 split, explains at paragraph 86 of the judgment:

“[T]he EU Treaties not only concern the international relations of the United Kingdom, they are a source of domestic law, and they are a source of domestic legal rights many of which are inextricably linked with domestic law from other sources. Accordingly, the Royal prerogative to make and unmake treaties, which operates wholly on the international plane, cannot be exercised in relation to the EU Treaties, at least in the absence of domestic sanction in appropriate statutory form.”

The effect of the judgment renders any Article 50 notification given by the Prime Minister to the European Council without Parliamentary approval legally ineffective as a matter of domestic law and EU law.[4] This is because such notification would also fail to comply with Article 50(1), which requires a Member State to withdraw from the EU “in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.”[5]

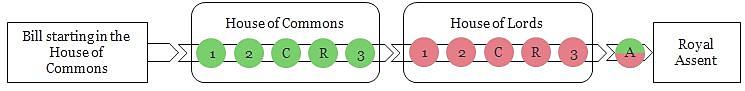

To pass an Act of Parliament, the Government will need to introduce a bill for the approval of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The bill becomes an Act of Parliament following the approval of both Houses and Royal Assent.[6]

Key:

1 – First Reading

2 – Second Reading

C – Committee Stage

R – Report Stage

3 – Third Reading

A – Consideration of Amendments

Figure produced using Parliament’s guide to the passage of a Bill (available here).

Prior to the EU referendum on 23 June 2016, 480 out of 650 MPs stated that they intended to vote to remain in the EU.[7] It is anticipated now, however, that the Prime Minister will be able to whip almost all Conservative MPs, save for the few expected hold-outs, to vote in favour of the Government's bill authorising the Government to issue a notification under Article 50. Jeremy Corbyn, the Leader of the Opposition, has previously indicated Labour’s willingness to prevent the Prime Minister from triggering Article 50 if she fails to agree with Labour’s “Brexit bottom line.”[8] This ‘bottom line’ includes, inter alia, access to the single market.[9] However, it was later clarified that Labour would not block an Act of Parliament but would rather seek to influence and amend the Government’s terms of negotiation.[10] Since this clarification, members of Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet have indicated their intention to refuse to vote for a bill to trigger Article 50.[11] This signals the willingness of some MPs to obstruct the passage of the bill through the House of Commons. Despite this, on 7 December 2016 the House of Commons voted overwhelmingly to back the Government’s plans to begin formal Brexit talks by the end of March 2017. This largely symbolic vote was not intended to provide a legal basis for the triggering of Article 50, nor is it binding on MPs. Nonetheless, it is indicative that it is unlikely that the House of Commons would ultimately block Brexit.[12]

However, as a result of today’s judgment, Parliament will have the opportunity to ratify the referendum, which may result in further debate into the manner in which the UK’s exit negotiations progress.[13] Parliament will be given a forum whereby it can have the opportunity to legitimately impose conditions on the Government’s negotiations.[14] These conditions may include, for example, the right to notice, comment and response.[15]

It is worth noting that Article 50 does not allow for a conditional or qualified notification.[16] Any conditions imposed by MPs in the House of Commons would dictate the UK Government’s negotiating stance as a matter of UK law. The imposition of such conditions may impact the agility with which the UK could conclude negotiations with the EU. Any agreement between the UK and the EU would ultimately be subject only to a European Council vote, as the Government retains the sole power to enter into international agreements on behalf of the UK.[17] However, Theresa May has stated that the Government will put the final Brexit deal to a Parliamentary vote.[18]

Revocability of an Article 50 Notification

Once the European Council receives the UK’s Article 50 notification, negotiations will begin to agree the terms of the UK’s withdrawal.[19] Some, including the cross–bench peer who drafted Article 50, Lord Kerr, have stated that they consider that any Article 50 notification is revocable.[20] However, no such express right to revoke a notification exists in Article 50.[21] All parties in Miller accepted that a notification under Article 50 is irrevocable, although this may have been a strategic move to avoid an appeal to the European Court of Justice.[22]

The composition of the House of Lords, many of whom have expressed strong anti–Brexit views, has the potential to cast uncertainty on the approval of the bill authorising the Government to issue a notification under Article 50.[23] Under the Salisbury/Addison convention, the Lords will not vote against measures which are contained in the manifesto of the governing party.[24] The 2015 Conservative election manifesto promised to “honour the result of the referendum, whatever the outcome”.[25] The combination of the Salisbury/Addison convention and the Conservative’s 2015 manifesto may ensure the House of Lords vote in favour of the bill, but this is a political and practical question as they are not bound to do so.

Whilst the Salisbury/Addison convention prevents the Lords from blocking or including wrecking amendments which remove substantial parts or change the effect of the bill, it does not prevent the Lords making amendments to the bill.[26] Any changes to the bill would be sent to the House of Commons for consideration.[27] This could result in the bill passing back and forth between the Houses, as both must approve its final wording (subject to the Parliament Act 1911, as discussed below). Ultimately, this could delay the Act of Parliament and the ability of the Government to give a notification under Article 50.[28]

Parliament Act 1911

Following the Parliament Act 1911, if a bill is passed by the House of Commons in two successive sessions and then rejected by the House of Lords in each of those sessions, it will receive Royal Assent and become an Act of Parliament without the consent of the House of Lords. This will take effect following the elapse of one year between the date of the second reading in the first session in the House of Commons and the date on which it passes in the House of Commons in the second sessions.[29] Therefore, a rejection by the House of Lords would only delay the passage of the bill. It could, however, frustrate Theresa May’s promise to trigger the exit process by the end of March 2017.[30]

In the event of a rejection or a significant delay by the House of Commons or the House of Lords, the following three outcomes are likely: (i) an early general election; (ii) a second referendum; or (iii) the resignation of Government. Any delays or increased uncertainty around Brexit will have a negative effect on the UK’s economy and it is hoped that the strength and stability of the UK’s economy will remain a key consideration during such political ambiguity.

Early General Election

The Government could call an early general election in order to gain a mandate from the electorate to trigger Article 50. The Fixed Term Parliaments Act 2011 (the “FTPA”) prescribes how general elections are called. It has transferred the power to call an election from the Prime Minister, using the royal prerogative, to the House of Commons.[31] It mandates the date for the 2020 election.[32] Assuming there was no attempt to repeal the FTPA (which would come with a host of additional constitutional complexities), the FTPA prescribes two instances in which an early general election can be called, being either: [33]

In the event that an early general election was called, political candidates in support of the campaign to leave the EU could be placed within each constituency. The results of the EU referendum showed that 258 out of the 382 voting areas recorded a vote share to leave the EU of more than 50%.[37] Although these voting areas do not map perfectly onto Parliamentary constituencies, pro–Remain MPs from any political party, or those who have voted to impose significant restrictions on the Government in a way which could be characterised as attempting to thwart the referendum result as some have threatened,[38] could struggle with re–election if the Vote Leave campaign were to put up pro–Leave challengers.

Second Referendum

By withholding their approval of the bill, Parliament could generate sufficient movement to justify a second referendum.[39] Parliament would have discretion in determining the substance of such referendum. The referendum on 23 June 2016 determined whether the UK should withdraw from the EU; it did not ask how, or on what conditions this withdrawal would proceed.[40] The second referendum could be used to answer these questions, although it would be difficult to set out any substantial conditions for approval in a somewhat binary manner. Additionally, the result of the second referendum could be made binding, unlike the first referendum,[41] and therefore require Parliament to respect its result and proceed with authorising the Government to issue a notification under Article 50.[42] At the moment, a second referendum is largely politically unsupported, although the Liberal Democrats have proposed a new referendum on the final terms of Brexit.

Resignation of Government

In the event that the bill is rejected or unduly delayed in either the House of Commons or the House of Lords, the incumbent Government could resign, or threaten to resign. The threat to resign may be enough to force Parliament to approve the bill, as any attempt to bypass the referendum result is likely to damage the public’s trust in Parliament.[43] The resignation of Government has never been an issue because prior to the FTPA the Government maintained the power of the royal prerogative to call a general election. The FTPA provides no clarity in the event of the resignation of Government; it only mandates arrangements for a vote of no confidence or a vote in favour of an early election by two-thirds of the House of Commons.[44] These provisions have never been exercised in practice; therefore it is unclear how the situation would be resolved due to its novelty. It may fall outside the scope of the FTPA and allow The Queen to exercise the royal prerogative to appoint a new Government. However in practice a “resignation” is likely to only actually take place by the House of Commons passing a vote of no confidence in the Government. If passed by simple majority, this motion would trigger the 14–day period to establish a new Government, failing which a general election will be called. Under the FTPA, this would enable the dissolution of Parliament and the appointment of a newly elected Government.[45]

[1] The royal prerogative is a set of powers invested in the Crown. These powers are non-statutory, but reflect historical powers reserved to the Crown, now in practice exercised by the Government, to take action without Parliamentary approval.

[2] R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2016] EWHC 2768 (Admin).

[3] Bypassing the Court of Appeal, pursuant to the leapfrog appeals procedure.

[4] Nick Barber, Tom Hickman and Jeff King, “Pulling the Article 50 ‘Trigger’: Parliament’s Indispensable Role”, UK Constitutional Law Association, 27 June 2016 (available here).

[5] TEU, Article 50(1).

[6] Royal Assent is nowadays a mere formality, and is assumed for these purposes.

[7] Rob Merrick, “Brexit: MPs will back Theresa May and trigger Article 50, a campaign group has predicted”, Independent, 3 November 2016 (available here).

[8] “Jeremy Corbyn: Labour will block article 50 if demands not met”, The Guardian, 5 November 2016 (available here).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Laura Hughes, “Jeremy Corbyn forced to clarify Labour will not block the triggering of Article 50”, The Telegraph, 6 November 2016 (available here).

[11] Heather Stewart, Anushka Asthana and Jessica Elgot, “Shadow cabinet MPs ‘considering’ voting against article 50”, The Guardian, 19 January 2017 (available here).

[12] Some MPs that campaigned to remain in the EU that have announced that they will respect the result of the referendum and would vote to begin the exit process. This number is sufficient to ensure the bill would be approved. (Iain Watson, “Could pro-Remain MPs and peers scupper Brexit?”, BBC, 4 November 2016, available here).

[13] Jeff King, “What Next? Legislative Authority for Triggering Article 50”, UK Constitutional Law Association, 8 November 2016 (available here).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] ] R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2016] EWCA 2768 (Admin), paragraph 10, (available here).

[17] Any agreement reached by the UK and the European Union will be voted upon by the European Council, acting via qualified majority. Votes held by qualified majority must be passed by representatives from a special majority of member states (usually 15 member states), representing a special majority of the total population of the EU (usually 65%). (The Council of the European Union, “Qualified majority”, 31 May 2016, (available here).)

[18] Theresa May, “The government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM Speech”, 17 January 2017, (available here).

[19] TEU, Article 50(2)

[20] Glenn Campbell, “Article 50 author Lord Kerr says Brexit not inevitable”, BBC News, 3 November 2016 (available here).

[21] Nick Barber, Tom Hickman and Jeff King, “Pulling the Article 50 ‘Trigger’: Parliament’s Indispensable Role”, UK Constitutional Law Association, 27 June 2016 (available here).

[22] David Feldman, “Brexit, the Royal Prerogative, and Parliamentary Sovereignty”, UK Constitutional Law Association, 8 November 2016.

[23] On 1 August 2016, Conservative peer Baroness Wheatcroft indicated that there was a majority in the House of Lords in favour of remaining in the EU. (“House of Lords could defy Brexit, peer claims”, BBC, 1 August 2016, available here).

[24] “Conventions of the UK Parliament”, Report Session of 2005-6.

[25] The Conservative Party Manifesto 2015, page 73, available here.

[26] “Conventions of the UK Parliament”, Report Session of 2005-6.

[27] “How laws are made”

[28] Simon Sapper, “The House of Lords has suddenly come into its own – white knights in ermine could rescue us from Brexit yet”, Independent, 4 November 2016 (available here).

[29] Parliament Act 1911, section 2(1).

[30] Theresa May, “Britain after Brexit: A vision of a Global Britain”, 2 October 2016

[31] Jon Stone, “Early general election: Can Theresa May actually call one?”, Independent, 12 July 2016 (available here).

[32] FTPA, s1(3).

[33] Jon Stone, “Early general election: Can Theresa May actually call one?”, Independent, 12 July 2016 (available here).

[34] FTPA, s2(1)(b).

[35] FTPA, s2(3).

[36] Jon Stone, “Early general election: Can Theresa May actually call one?”, Independent, 12 July 2016, (available here).

[37] House of Commons, “European Union Referendum 2016”, Briefing Paper Number CBP 7639, 29 June 2016, page 10.

[38] ITV Report, “Increasing number of MPs set to vote against triggering Article 50”, 11 November 2016.

[39] Mark Chandler, “Brexit: House of Lords could delay Article 50 and trigger second EU referendum, Tory peer claims”, Evening Standard, 1 August 2016 (available here).

[40] Jeff King, “What Next? Legislative Authority for Triggering Article 50” UK Constitutional Law Association, 8 November 2016 (available here).

[41] Haroon Siddique, “Is the EU referendum legally binding?”, The Guardian, 23 June 2015 (available here).

[42] This was the case under the Alternative Vote Referendum. The legislation passed before that referendum, the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011, required an order to be made bringing into force the alternative voting provisions if more votes were cast in the referendum in favour of the answer “Yes” than in favour of the answer “No” without further Parliamentary involvement.

[43] “Brexit: Ignoring Leave vote would be outrage MPs told”, BBC, 5 September 2016 (available here).

[44] FTPA, s2.

[45] FTPA, s3.

Industries

Regional Experience